WebKit has made some serious news by finally implementing the srcset attribute. As Chair of the W3C’s Responsive Images Community Group, I’ve been alternately hoping for and dreading this moment for some time now. It turns out to be good news for all involved parties—the users browsing the Web, most of all.

As with all matters pertaining to “responsive images”: it’s complicated, and it can be hard keeping up with the signal in all the noise. Here’s what you need to know.

What Does It Do?

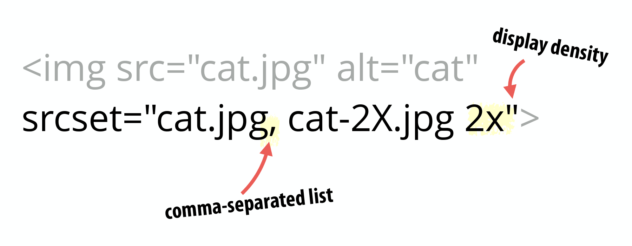

As originally proposed, the srcset attribute allowed developers to specify a list of sources for an image attribute, to be delivered based on the pixel density of the user’s display:

<img src="low-res.jpg" srcset="high-res.jpg 2x">Not too scary, this markup. In plain English:

“Use low-res.jpg as the source for this img on low-resolution displays, and for any browser that doesn’t understand the srcset attribute. Use high-res.jpg as the source for this img on high-resolution displays in browsers that understand the srcset attribute.”

Things were starting to look scary, for a little while there. Due in part to high resolution devices, the average website is now nearly an entire megabyte of images. Now developers can target users on high-resolution displays with a high-resolution image source. Meanwhile, users on lower pixel density displays won’t be saddled with the bandwidth cost of downloading a massive high-resolution image, without seeing any benefit.

Can’t We Do That With JavaScript?

On the surface, srcset isn’t doing anything special—it chooses an appropriate source from an attribute and swaps the contents of an img tag’s src. Swapping the contents of an attribute is something we’ve been doing with JavaScript since time immemorial. Well, since the 90s, anyway. So, what does this gain us?

We actually attempted this approach on BostonGlobe.com, one of the earlier sites to make use of any sort of “responsive images” solution. Thanks to increasingly aggressive prefetching in several of the major browsers, an image’s src is requested long before we have a chance to apply any custom scripting: we would end up making two requests for every one image we displayed, defeating the entire purpose. I’ve documented some of those efforts elsewhere, so I’ll spare you the gory details here.

Can’t We Do That With CSS?

“Yes” and “No.” We can do this with background images easily enough, using a combination of media queries concerned with pixel density. srcset as implemented by WebKit is very similar to the recent image-set feature they introduced to CSS. image-set allows you to specify a list of background image sources and resolutions and allow the browser to make the decision as to which one is most appropriate—pretty familiar stuff. We didn’t have anything along these lines for non-presentational content images, however, until now.

Using CSS to manage content images is broken by default, in terms of keeping our concerns separate. It’s an approach that may make perfect sense within the scope of a quick demo page, but stands to quickly spiral out of control in a production website. Having our CMS generate scores of stylesheets full of background images would be no picnic, from a developer standpoint. Worse, however, is that it would lead to requests for stylesheets and images that users may not need unless done very, very carefully. Beyond that, it renders our images—no pun intended—inaccessible to users browsing by way of assistive technologies.

The closest thing we’ve found to a CSS-based approach would swap an image’s sources based on values set in HTMLs data attributes, using some proposed CSS trickery, much of which is only theoretical and may never happen. However, it still didn’t account for the the double download of high and low resolution image assets—the same issue we encountered with JavaScript. Even if a technique like Nicolas’ should become available to us, we’ll still face the same problems as many script-based solutions: attempting to work around a wasteful, redundant request.

What Does It Do About Bandwidth?

Regardless of screen density, there are a number of situations where lower resolution images sources may be preferable: a Retina MacBook Pro tethered to a 3G, for example, or an unstable conference WiFi network—both situations we’ve all been in plenty of times.

Beyond simply providing us with a sort of inline shorthand for resolution media queries, srcset accounts for bandwidth as well, in a sense. It’s buried in arcane spec-speak, but one of the really exciting facets of srcset is that it’s defined as a set of suggestions to the browser. The browser can then use environmental heuristics or a user preference to decide that it wants to fetch a lower resolution image despite a high-resolution display: envision a preference in your mobile browser allowing high-res images to only be requested while connected to WiFi, or a manual browser preference allowing you to only request low-resolution images when your connection is shaky.

Ideally, we’d love to send only those images to devices which are specifically resized for each screen resolution. The intention is to save bandwidth and allow the images to download faster on the targeted screen. A common use case for responsive images.

This isn’t a part of WebKit’s early srcset implementation, but it does pave the way for their addition without requiring any changes to our markup. We, developers, can safely use srcset today, and these optimizations may come “for free” in the future.

What Does This Mean For The picture Element?

Here’s where things get interesting.

The version of srcset implemented by WebKit matches the original proposed use of srcset, and the version that the Responsive Images Community Group has been working towards. We can think of this incarnation of srcset as shorthand for the whole slew of media queries concerned with resolution, with one key difference where the browser can choose to override the applicable source based on user preference.

While this implementation matches the original srcset proposal, the current srcset spec attempts to expand the syntax to cover some of the use cases that the picture element fulfills, using a microsyntax that performs some—but nowhere near all—of the functions of media queries.

<img src="fallback.jpg" srcset="small.jpg 640w 1x, small-hd.jpg 640w 2x, large.jpg 1x, large-hd.jpg 2x" alt="…">In our opinion not ideal, this markup pattern. We’re restricted to the equivalent of max-width media queries, pixels, and an inscrutable microsyntax, all for the sake of duplicating the function of media queries. Fortunately for us, neither Web developers nor browser reps are particularly fond of this overextended syntax—hopefully, it will never see the light of day.

The picture element exists to address these use cases using a more flexible—and familiar—syntax. picture uses media attributes on source elements, similar to the video element. This allows us to target image sources to a combination of factors: viewport height and/or width, in pixels or ems, using either min or max values—just like media queries in our CSS.

<picture>

<source src="med.jpg" media="(min-width: 40em)" />

<source src="sm.jpg" />

<img src="fallback.jpg" alt="" />

</picture>

The picture specification was written with this reduced srcset syntax in mind, so it could be used on picture’s source elements as well as img elements.

<picture>

<source srcset="med.jpg 1x, med-hd.jpg 2x" media="(min-width: 40em)" />

<source src="sm.jpg 1x, sm-hd.jpg 2x.jpg" />

<img src="fallback.jpg" alt="" />

</picture>In concert, the two markup patterns give us an incredible amount of flexibility over what image sources we serve to users, depending on their context.

So This Is Good News.

Absolutely, it is. While srcset as implemented by WebKit doesn’t address to all the responsive images use cases, it does represent a major step toward a long overdue solution—hopefully the first of many.

Let’s hope that other browsers follow WebKit’s lead in implementing this feature as it was originally proposed, and stay tuned to the Responsive Images Community Group’s homepage and Twitter account to keep tabs on the subject.

I also wrote about the issues with responsive images and the solutions we’ve come up with when working on the BostonGlobe website in the chapter “The Struggles and Solutions In Responsive Web Design” of the upcoming Smashing Book 4. Grab it, you won’t be disappointed.

(vf)

Source: Smashing Magazine